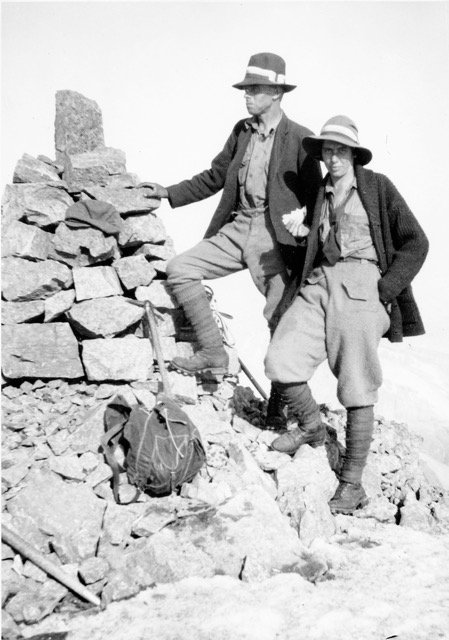

Phyllis & Don Munday, 1925, peak of Mt Victoria, Canadian Rockies. Photo courtesy of MONOVA: Archives of North Vancouver, #5650.

“Mistakes will happen”, remarked 89-year-old Phyllis Munday in 1983, from her North Vancouver Tempe Crescent home, upon reading her own obituary in the Vancouver Sun, which had inadvertently assumed the death of 93-year old Phyllis E. Munday of White Rock was the mountaineering Phyllis Munday of North Vancouver

But Phyllis and her climbing-partner/husband, Don Munday, could literally not “put a foot wrong” as they conquered mountain after mountain in their North Shore backyard and beyond, becoming more and more intrepid with some of the most technically challenging climbs, even by today’s standards.

The pinnacle (pun intended) of their climbing adventures had to be when they set out in 1926 and again in 1928, to solve the mystery of a towering, then unknown mountain - dubbed Mystery Peak by the Mundays – which Phyllis had spied from the top of Mount Arrowsmith on Vancouver Island in 1925. What they discovered was later named Mount Waddington. It is the highest peak of BC’s Coastal range (13, 186 feet) and the highest peak that is entirely in BC. It is described by many as among the world’s most challenging mountains, being remote and incredibly inaccessible with unpredictable weather.

If we go back to 1926 and 1928, when Phyllis and Don Munday set off to find and conquer their “Mystery Peak”, the ice-capped Mount Waddington was completely uncharted territory and yet this incredible, intrepid couple, burdened with heavy gear and provisions, made their way in a rowboat and then on land, bush-whacking through dense forests, felling trees to make bridges, until their ascent of the glaciers in 1928 took them to the summit of its northwest peak. Today the standard approach is to fly into the area by helicopter which makes their 1920’s trips all the more remarkable.

Another notch in Phyllis’s climbing pick, happened in 1924, when Phyllis became the first woman to climb to the peak of Mount Robson, the highest mountain in the Canadian Rockies!

Born Phyllis B. James in (Ceylon) Sri Lanka, 1894, she was the daughter of a Lipton tea planter, Frank James, and his wife Beatrice, both from Cornwall, England. Between the year of her birth and age 14 Phyllis lived in Sri Lanka, England, the Canadian Prairies, Nelson BC and then the Kokanee area of B.C. before the family settled in Vancouver. In 1910, the teenager Phyllis founded the first Girl Guide Company in Vancouver and she went on to be a lifelong Guider. Today, at West Vancouver’s Lighthouse Park, Girl Guides still have the benefit of the Phyl Munday Nature House – named after Phyllis for being a dedicated Girl Guide leader, a naturalist and an extraordinary mountaineer. And while her father had hoped she would follow him in his passion for the game of tennis, with its precise rules and protocols, his daughter had much higher, wilder aims and passions.

On the right, Girl Guide Company Leader, Phyllis Munday on Grouse Mountain in 1912. Photo courtesy of MONOVA: Archives of North Vancouver, #5655.

Mount Munday in the Coastal Range is named after Phyllis and Don as is the Munday Alpine Snowshoe Park on Grouse Mountain, an area where the Mundays frequently climbed, a century before today’s Grouse Grind. As newlyweds, they lived in a small cabin, built by Don, on nearby Dam Mountain. After an early morning marriage ceremony at Christ Church Cathedral in February 1920, they quickly changed from wedding finery into climbing attire and before noon were on the ferry to Lonsdale to make their way to the cabin, their honeymoon destination. In 1927, six years after the birth of their daughter Edith, they moved to 162 Kings Road West in North Vancouver. In 1930, a building permit for 373 Tempe Crescent was taken out by an E.L. Mundy (sic) and Don Munday is listed as the home owner in 1931; Phyllis’s name was added as his wife in 1933, when wives’ names began to appear in the City Directories. Phyllis lived in their home until 1985, thirty-five years after the death of Don.

Phyllis snowshoeing on Grouse Mtn Plateau– 1924 – Photo courtesy of MONOVA: Archives of North Vancouver, #5653

Phyllis was a truly extraordinary woman whose valued achievements amount to significant, positive contributions to the North Shore and to British Columbia. By the end of her life Phyllis had received the Order of Canada and was an important and influential presence in the world of Girl Guiding, who awarded her with the movement’s highest honour, the Bronze Cross, for her valour in the rescue of a teenage boy. It was yet another in a list of firsts for her, being the first Canadian to receive the honour. In 1967, she was accorded the highest honour conferred by St John Ambulance Brigade, Dame of Grace. In 1983, the same year her obituary was inadvertently published while she still lived, the University of Victoria awarded Phyllis an honorary degree for her contributions to “the conservation of our natural heritage” and in 1998, eight years after her death, Canada Post issued a Phyllis Munday stamp.

A short film* survives of 89-year-old Phyllis Munday sitting in a big, floral patterned, armchair in her Tempe home. She is in conversation with the late Olga Ruskin. Her memory is sharp and her words precise and there are glimpses of the young and intrepid mountaineer in the older woman. As she speaks, we discover that she and her husband Don were accomplished photographers who themselves developed much of the outstanding black and white photographic record of their pursuits. In the photos we see her attired in britches, not considered suitable attire for a woman at that time. Never held back by others’ expectations, she simply wore a skirt over the britches to the base of a climb, then stored the skirt under a log until her return. The way to climb a mountain, she asserts in the film, is one foot after another at a steady pace wearing good boots, with three pairs of socks, and carrying in your pack suitable provisions and equipment such as a rope and ice axe. Unlike today’s choice of lightweight, waterproof outdoor equipment, they made most of what they used and their tightly packed packs were heavy, often 70lbs or more. Asked about the pack in the photograph below, with two-year old Edith by her side, Phyllis explains that while she is indeed carrying a heavy pack, on top of it are stacked two chairs that she was taking to their Dam Mountain Cabin. They often camped when on climbs, but not under canvas. The sail silk tents they used were designed by Don and cut out and sewn together by Phyllis. For a woman whose head was often in the clouds, Phyllis was completely down to earth!

Phyllis with daughter Edith, outside Dam cabin carrying a 58lb pack and chairs, 1923, Photo courtesy of Monova: Archives of North Vancouver, #5652

In North Vancouver, there is a street named Munday Place, which is part of a maze of streets in the Tempe subdivision. Some might find it a surprising choice for honouring such celebrated mountaineers, since the street and the entire sub-division is more or less flat as a pancake! Munday Place sits a 10-minute stroll downhill from 373 Tempe Crescent, where the very house that this remarkable woman occupied for close to six decades still stands. The house at 373 Tempe Crescent gives no indication of its significance as the Phyllis Munday Residence; there is no plaque bearing her name and no Munday Trail at the steps from Tempe Crescent down to the subdivision and Munday Place. Nor does the house appear on the City of North Vancouver Heritage Register. Mistakes will happen, Phyllis once said. It could be a simple mistake or oversight that the house where she lived is has not been recognized by the City of North Vancouver as having heritage significance. I however believe that 373 Tempe Crescent should be recognized, not for its architectural attributes – although it is striking - but because it was Phyllis Munday’s residence and because Phyllis Munday was an iconic North Vancouver woman!

373 Tempe Crescent, March 2022.

Video Interviews:

* The late Phyllis Munday in conversation with the late Olga Ruskin. Rogers Community TV, Pioneers and Neighbours (1982)

Part 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TwYykRd1HCk

Part 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rWVUTaihdro

.